COPYRIGHT CITY SANCTUARY THERAPY

No part of this website, including the blog content may be copied, duplicated or reproduced in any manner without the author’s permission.

Any information, materials, and opinions on this blog do not constitute therapy or professional advice. If you need professional help, please contact a qualified mental health practitioner.

What is Parentification?

In simple terms, parentification is when a child is given duties and responsibilities that are not age appropriate. Parentification can occur in two different forms- emotional and instrumental. Some people experience one of the other, while others experience both. Emotional parentification is when the child provides emotional support to the adult, while instrumental parentification is when the adult assigns and ascribes adult roles and duties to the child. In practice, the adult may simply off load onto the child, confide in the child, ask questions about life situations, seek counsel, & solicit advice from the child. It can also occur when a child is given adult chores, and tasks that are not age appropriate. When this happens, there is a role reversal where the child becomes the adult, the provider of emotional containment to an adult (care taker), and an involuntary provider of practical support. Many a time parentification happens covertly, and the adult may not recognise their emotional and practical dependence on the child. In any situation where there is parentification, there is neither sensor in the adult, nor a recognition of boundaries of what is appropriate, and what is not. Children do not only grow and develop physically, they also develop psychologically; they have certain milestones they need to reach and accomplish. Parentification interferes with the natural psychological development of the child, and impinges on the accomplishment of their own developmental tasks, as they are pivoted into adulthood.

When and why does Parentification happen?

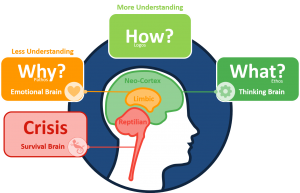

Parentification typically occurs in parent-child relationships, and it also occurs in families where where there is an older sibling who has to look after the younger ones practically and/or emotionally. What is typical is that in emotional parentification, the adult emotionally confides in the child, and speaks to the child about challenges they may be having in their life-for example financial difficulties, marital difficulties, health difficulties, relationship problems, and other life situations. These things may seem insignificant to the adult, however, they are emotionally burdening the child who has no capacity to understand, make sense, or emotionally process them. Another way emotional parentification happens is when the child grows up in an environment where they have to tune into the adult’s emotions, in order to protect themselves and feel safe. This is likely to happen when there is one or both parents who is emotionally volatile, and where there are parents who engage in regular fights, leaving the child to intervene and become the peacemaker. The child has to deal with complex emotions and put in the adult role when this happens, which becomes parentification.

With instrumental parentification, the child takes on and assumes adult roles. They are made to do things that are beyond their capacity as children, therefore not age appropriate. This may be as simple as dealing with household chores, looking after their siblings, cooking, shopping, or budgeting, which undermines their own experience as a child. Some parents do struggle to distinguish healthy coaching of a child to do household chores with parentifying a child. While it’s not a bad thing to teach children life skills, it is harmful when they are made to do them repeatedly, and it becomes their duty.

Emotional parentification is very common in families where there are marital problems- divorce or separation, or any other marital discord. You find that either one or both parents use the child as a confidant of their problems, and share feelings about the marital issues or the other parent. The parent relates to that child “as if” they are an adult. This phenomenon is also common in single parents with children who become a replacement of the lost partner, and used as a surrogate partner emotionally. In actual fact, the adult is committing emotional incest with a child, as they are not their partner, but a child. Although the adult may not recognise the burden of emotional dumping, it is the child who is impacted by it & needs to make emotional adjustments to accommodate the adults’ feelings, while neglecting their own. Children are very compliant, they simply shut off their own feelings, and look after the adult; the adult becomes complicit in neglecting the child’s feelings. In the child’s mind paying attention to the adult’s feelings is the right thing to do. However, it also means the child’s feelings are unattended to, and unprocessed, and this does create confusion in their minds.

Parentified children are likely to develop what Winnicott (1960) would term a “False Self” organisation. According to Winnicott, this False self is a defensive organisation which the child builds, as a result of the parents’ repeated failure to meet the child’s emotional needs (omnipotence). In compliance with the mother, the child develops this False self, which protects the True Self. The False Self is inauthentic and it is not as confident, as it is a defensive organisation which shields the more robust and authentic True self, which was never allowed to develop.

Parents who parentify their children are adults who are likely to be isolated & not have much support around them, hence their reliance on a minor for emotional and practical support. The parent who parentifies their child/children lacks boundaries, and psychologically immature to appraise what is right or wrong.

Signs of Parentification in adult life?

Parentification is a hidden trauma, that can get easily missed, yet it has such a profound impact on the individual. Most of these difficulties create real challenges in interpersonal and romantic relationships. Parentification is not gendered, both men and women experience it. However there are certain cultures where some parents have more porous boundaries with their children, which lends them to being more easily parentified. Other socio economic factors also play a part in Parentification. For example it’s common practice in immigrant families for the older siblings to look after their younger ones, while the parents are at work.

Here are some of the signs that people who have been parentified display in adult life

- People who have been parentified as children are likely to become adults who are insecure, and have an impoverished sense of self. They lack confidence in themselves, and find it difficult to advocate for themselves, and look after themselves, prioritising others-typical people pleasers. This is so because of the False self organisation as discussed above.

- People who are parentified are likely to have difficulties with boundary setting, and unlikely to honour their boundaries. This is so because their own boundaries were violated by their parents, and had their own needs neglected. They never learnt to develop healthy boundaries. Parentified adults are also likely to breach other people’s boundaries and jump in to “fix” other people’s problems, at times unsolicited. This is simply a repetition of what they grew up doing for their parents in their childhood.

- Parentified adults often experience difficulties defining their needs, and expressing them, as well as difficulties expressing their own feelings which are seen as secondary to others and insignificant. This is simply a manifestation of an internalised way of relating to other’s where other people’s needs takes priority- they emotionally looked after their parents or older adults around them, and they repeat the same.

- Adults who were parentified as children are likely to experience intense feelings around rejection, and they often hold onto to unhealthy relationships to avoid feelings of rejection and loss. This is so due to the poor sense of self as a result of the False self organisation.

- Emotionally parentified adults may be conflict avoidant. This is so because for them, serving others and not “rocking the boat” means they can maintain relationships, and this gets done relentlessly, to one’s own detriment. It’s as if they are buying love, at all costs. They do this because they have learnt to keep their environment in control and not to ‘rock the boat’. This way of functioning is harmful in interpersonal and romantic relationships. By avoiding conflict, conflict avoidant people are easily manipulated, abused and exploited in both romantic and non romantic relationships.

- Parentified adults tend to have insecure attachment styles -Avoidant or Anxious attachment (Bowlby, 1969). This is so because they had to detect the level of proximity with their care givers- in order not to be abandoned and at the same time, protect themselves. Anxiously attached people tend to engage in push and pull dynamics, oscillation between intensity, and withdrawal. Avoidant people are likely to keep a distance from others, despite yearning for connection.

- Parentified adults tend to struggle with intimacy and maintaining long and stable connections. Having been put in the role of emotionally caring for an adult/s, they associate intimacy with being suffocated, curtailed and engulfed. They value their independence and autonomy; however this can be a way of keeping others at a distance and avoiding intimacy which is viewed as engulfment. While they may seek emotional connections with others parentified adults tend to struggle with longevity in relationships, and seek new experiences which perpetuates the cycle of avoidance.

- Parentified adults tend to become controlling of their partners or life in general. They like things to be under their control and done in a particular way. This is a way of mitigating anxiety of things going wrong. This role is familiar-they had to keep things under control for their parents and or siblings.

- Parentified adults engage in relationships where they emotionally and physically look after other people. This can lead to co-dependent dynamics or parents- child dynamics in romantic relationships. The parentified adult is likely to be the caretaker and infantilise their partners.

- Parentified adults are likely to experience anxiety and depression, because of the inability to fully express their feelings and emotions. Emotions make life colourful and rich, Without a heathy expression of emotions we tend to internalise our feelings. Certain feelings such as anger, frustration, and sadness, when internalised, become toxic and can lead to depression, anxiety as well as anger issues.

Should I confront my parents about parentification?

Revisiting the past and confronting one’s parent can be a double-edged sword. It depends on various things, including the quality of relationship with the person/s involved. It may evoke compassion and be a catalyst of a healing journey for both involved, or it can create friction. Parents tend to become defensive when they are made to feel like they failed, or they are being blamed. If the emotional dumping and violation of boundaries continues in adulthood, one can mention this to the parent and have a “boundary conversation” where you as an adult are redefining your relationship boundaries with the parent. This does not have to be antagonistic, but a gentle conversation that can bring understanding, insight, and healing to both. The difference is that this time there are two adults, not a parent and a child. This may help the parent to start thinking about their own process, and their role which can make them change their behaviour and acknowledge its impact. In most occasions, these behaviours stem from a very unconscious place as these parents are people who had their own boundaries violated as children. Parents are people who were parented themselves, and once upon a time they were children. No one has a blueprint for parenting. The parents may not be aware of this repetition, and the fact that they are simply re-enacting their own trauma with their own parents. Having insight into this and acknowledging it is the onset of the healing and breaking these negative cycles.

Healing from Parentification

- If you suspect that you were parentified, the first thing is to reflect on the relationship with your parents, and significant others from your childhood. It is likely that in adult life these significant others may continue to violate the emotional boundaries, in the same way as they did.

- Where there was parentification in childhood, the adult tends to be drawn back into the caring role, and often these are adults became their parents’ own parent’s and develop co-dependent relationships. Healing could be as simple as stepping back from these relationships and creating space -this is indeed a form of self-care and breaking the unhealthy pattern. It could be simply saying no to certain things you would normally agree with or agree to do in-service of others. It could simply be doing the things that you like doing without worrying what others may think or say, or without seeking their permission.

- A key step towards healing lies in setting boundaries as an adult who understands things differently to the child and start learning to prioritise one’s own needs. Being able to recognise how one feels, validating those feelings, and beginning to express them without the fear of hurting the other person is crucial. Without doing that, we simply repeat the same cycle of looking after other’s needs, neglecting ours, to our own detriment.

- A crucial aspect of healing from emotional parentification is learning to tolerate intimacy and reciprocating care. Instead of running away and/or avoiding intimacy, learn to be present and bear the feelings closeness brings up. Its also a part of learning to be cared for emotionally while caring for the other- reciprocity.

- Therapy is the gateway to emotional healing where the trauma of parentification can be explored, understood and processed in a healthy and meaningful way.

References

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Winnicott, D.W. (1960). Ego distortions in terms of True and False Self: The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. Karnac Books: UK

Main Image Credit to Kamran Chi- Unsplash