COPYRIGHT CITY SANCTUARY THERAPY

No part of this website, including the blog content may be copied, duplicated, or reproduced in any manner without the author’s permission. Any information, materials, and opinions on this blog do not constitute therapy or professional advice. If you need professional help, please contact a qualified mental health practitioner.

I wrote this publishable paper as part of my professional Doctorate which was a taught Doctorate, consisting of 8 assignments and a 50 000 word thesis. Unusual, considering that most PHDs and Doctorates, (with the exception of Clinical Psychology and a few others), only comprise of research modules, and the main thesis.

The publishable paper was wrote for publication in the Journal of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. While it passed, and met the publication requirements, l never got round to publishing it. Time being one of the major constraints, and to be frank, the antipathy to peer reviews.

I had to add this paper to my blog as the matters discussed in it are very close to my heart as a perpetual student myself, lecturer, and psychotherapist.

Modality should not be the guiding factor in any therapy. It should be the client’s needs that guides the therapist. CBT and psychoanalytic oriented therapies are often pitted against each other, yet in reality they inform each other.

Delivering Psychological Therapies to University Student Client Groups: Does Modality Really Matter? An Attachment Perspective

Abstract

Leaving home to begin University studies can be a very challenging experience for some students, due to the external, physical separation and the internal loss, resulting from the disruption of vulnerable attachment patterns. Some students seek psychological interventions through the University Student Psychology Services because of the sudden emotional distress they experience. Since the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2009) guidelines identify Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) as the first line of treatment for common mental health problems, this is the therapy which is regularly prescribed, even for those students who may be struggling with attachment and loss issues. Whilst recognising the valuable contribution of CBT in mental health provision, I would argue that cases like those identified above are better understood and reframed from an attachment perspective (Bowlby, 1969) and therefore best approached using a psychoanalytic, clinical framework, which addresses loss and mourning (Freud, 1917) and includes interpersonal relationships, unconscious processes and affective qualities (Lemma, Target, & Fonagy, 2010; Shedler, 2010). A single vignette will be presented, as an example of the typical student client group psychopathology, illustrating the therapeutic process. The name of the university and the client’s identity are not disclosed.

Key words: Loss, Attachment, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Adolescence, Psychoanalysis

Difficulties some students experience when leaving home to start University

The external reality of moving away from the family home to attend university is often consciously experienced as being very liberating. It signifies the beginning of a new life in a new environment, forming new friendships, developing independence, perhaps developing sexual relationships and creating an adult identity. However, the internal reality is that the experience can be very traumatic for those students who have not relinquished their infantile object relationships and who are insecurely attached. This is because leaving home not only involves physical separation, but the loss of the familiar environment, emotional displacement, challenges to established attachment patterns and loss of the family as a secure base (Bowlby, 1969). Bowlby (1973), postulates that attachment patterns are ‘internal working models,’ which he believes “represent an accurate reflection of the experiences of individuals” (p. 235).

In recent years, we have seen increased awareness of mental ill health problems in UK universities and even the suggestion of a ‘suicide epidemic’ among first year undergraduates. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-36378573reported an increase in self-harm incidents and suicides in first and second year UK undergraduates. The findings of this BBC report and others seem to suggest that these cases were the result of the stress related to leaving home and a potential breakdown of attachments. It is unlikely that academic difficulties were a major factor, as all undergraduates have met rigorous criteria to achieve university admission. We cannot totally discount the ‘small fish in a big pond’ aspect, which may negatively impact on someone who has been outstanding in their former school and is now surrounded by other high achievers. I suggest that the internal loss and challenges in attachments which the students experience because of leaving home makes them extremely vulnerable. If these issues are not understood and dealt with adequately through appropriate therapy, they can escalate, resulting in severe mental illness and, in extreme cases, suicidal actions. Such cases illustrate the potential gravity of the impact that leaving home can have on some students.

Recognition of the increasing incidence of mental ill health problems within the student population has led universities in the UK to invest in psychological therapy services, which mirror Improving Access to Psychological Therapy (IAPT). Traditionally, the model of choice was psychoanalytic, but today there is gravitation towards CBT, because of the NICE guidelines. This means that most students who are seen in student counselling services are prescribed CBT. The majority of therapists in the service now have to be trained to deliver the minimal, low intensity CBT in order to meet this need. The apparent mental health crisis in the undergraduate population suggests an urgent need for practitioners to engage with the root cause of the problem, which I believe is the internal impact of breakdown of attachments and that focusing on symptom management, whilst producing some undeniable benefits, offers only a partial solution to the problem.

Most of the students seen for therapy in universities are in late adolescence or early adult stage of development. Lamb, Hall, Kelvin, and Van Beinum, (2008) declare that in the UK we need to recognise the importance of providing psychotherapeutic services to the adolescent and young adult population during their transition into adulthood because the complexities of this developmental stage render the age group particularly vulnerable. This highlights the need to provide a space for the individual to understand their loss, to explore attachment patterns and to reflect on their interpersonal relationships. The therapeutic relationship can also be used as a basis for the student to learn how to build healthy relationships, as well as relinquishing broken attachments. I would argue that a psychoanalytic approach, which allows an exploration of interpersonal relationships, loss, mourning the experience of leaving home and reflecting on the breakdown of attachments, offers the only best way to resolve the internal problems.

CBT approach and NICE Guidelines

Following the Layard report (Layard, 2006), short term, manualised therapies, such as CBT, that are considered to be evidence based are now widely adopted. NICE has recommended CBT as the gold standard treatment model for most common mental health problems (DOH, 2009). Psychoanalytic oriented therapies appear to have fallen out of favour. Most of the CBT evidence base has been gained using Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), which many psychoanalytic clinicians view as unsuitable in assessing the process and outcome of psychoanalytic oriented therapies (Taylor, 2010; Shedler, 2010; Hinshelwood, 2010; McLeod, 2011; Cooper, 2011). NICE recommendations have therefore inadvertently hindered the dissemination and delivery of psychoanalytic oriented therapies in the UK.

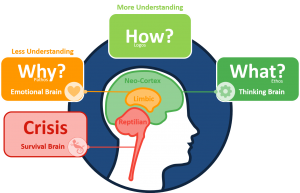

Somewhat ironically, CBT was developed by Beck, a psychoanalyst, and has its origins in psychoanalysis, despite it being out of step with psychoanalytic informed therapies (Beck, 1995; Knox, 2013). CBT, a behavioural model, assumes that the way we think (cognition) affects the way we feel (affect) and behave. The hypothesis is that by altering one’s maladaptive thinking and developing flexibility, one can reverse the cycle and change the way we feel (cognitive change). CBT focuses on acute symptoms and the external world. It does not seek to understand the cause or origins of the symptoms. The use of cognitive change methods, self-management skills and the adoption of behavioural strategies to counter maladaptive behaviour are considered key in the CBT model. Clients are actively required to use a range of tools in and out of sessions, with considerable emphasis on recording their thoughts and reflecting on them (Greenberger and Padesky, 1996). Most importantly, clients must be able to consciously access their thoughts and feelings.

The CBT model is manualised; it requires careful planning, and clearly identified desired outcomes. Experiments are a common tenet of the CBT model. Clients are encouraged to have graded exposure to their phobias and aversions, to systemically desensitise them (Leahy, 2003). Significantly, there is a teaching element in CBT delivery; the therapist must teach the client the model and how to use the techniques and tools. The psychotherapist’s role is therefore helping the individual to identify their negative cognitions or distorted belief systems and to be able to evaluate their own behaviour (Beck, 1995). CBT requires the use of monitoring tools – (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, and Löwe, 2006) Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), (Kroenke, Spitzer, and Williams, 2001) Physical Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), session by session.

Psychoanalytic approach and why it is most appropriate for the student client group

The significant decline in the delivery of psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies has mainly been due to the NICE guidelines assertion that CBT is more empirically evidence based than other approaches (NICE, 2009). Shedler (2010) states that the poor evidence base of psychoanalytic oriented therapy is not because of its ineffectiveness, but stems from the “poor dissemination of research and the arrogance and elitist attitude shown by traditional psychoanalysts who shunned research and inter- disciplinary working” (p. 98). Psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies, however, still have an important role to play clinically. Unlike CBT, they allow an exploration of the client’s interpersonal difficulties and of their internal world, which are key elements when working with the student client group. Norcross (2005) argues that psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies have positive outcomes which go beyond symptom prevention, which is the goal of CBT.

Psychoanalytic theories have their origins in the work of Freud, who initiated the theory of the unconscious (Freud, 1915). Despite the apparent differences in contemporary Freudian schools of thought, what underpins them all is the belief in the unconscious world, the importance of early life experiences and the psychopathology that can occur because of disturbances in the parent-infant relationship. Psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies are fundamentally centred in working with the transference in the analytic space. This analytic space between the therapist and client is used to explore unconscious processes, with the transference relationship acting as a catalyst to generate an understanding of the interpersonal effects. Through the experience of psychoanalytic oriented therapy, clients learn to build inner resources (Shedler, 2010).

The building of a therapeutic alliance between the client and therapist is vital. It enables clients (students) to build trust and gain confidence in others, an important aspect of interpersonal relationships. The therapeutic alliance is considered most crucial in psychoanalytic oriented therapies and central to its success (Orlinsky and Howard, 1986; Shedler, 2010; Safran, Muran, and Eubanks- Carter, 2011). Most of the students’ client group present with issues related to complexities of navigating from their infantile object relationships to adult and romantic relationships. In the psychoanalytic context, the transference relationship between the therapist and student can be used to trace the source of the disturbed infantile object relations, which might be the underlying cause of difficulties in current relationships.

Interpretations also play a major part in psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies; they enable the mutative links between the past and the present. Malan’s triangle of conflict, which focuses on past relationships, current interpersonal relationships and the ‘here and now’ (Malan, 1995), allows psychotherapists to formulate approaches which enable them to assist clients in comprehending the nature of their internal difficulties. These approaches render psychoanalytic psychotherapy more relevant and effective than CBT, when working with the student client group.

Psychoanalytic psychotherapies readily offer the invaluable space in which to explore loss and mourn the loss of attachments (Bowlby, 1969), which CBT does not. The notion of gaining insight into unconscious drives is what makes psychoanalytic oriented therapies more effective than other treatments (Norcross, 2005; Shedler, 2010). Fonagy (2015) argues that psychoanalytic treatments provide a unique window on human behaviour and the theories are rich and imaginative in developmental, clinical, and applied accounts.

CBT focuses on symptomology, while a psychoanalytic framework creates a space where difficult experiences can be safely explored and complex feelings expressed. Psychoanalytic oriented therapies also help the client to conceptualise their problem and situate it, thereby helping them build internal resources and reach beyond symptom remission. Shedler (2010) argues that the reason many therapies are successful is because they use techniques which are centred in psychoanalysis. This raises questions about the NICE recommendation of CBT as a panacea for common mental health problems. Psychoanalytic psychotherapies that seek to address the client’s internal world allow mentalization and in-depth exploration of the nature of the client’s difficulties, elements which are not covered when using the CBT model, suggesting that psychoanalytic therapies are appropriate when working with the identified student client group.

Loss through leaving home and the disruption of attachments

Attachment patterns are established at an early stage and are centred in the relationship between the infant and its primary care giver (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth, 1973). Leaving home, separating from siblings, other family members and friends seems to result in a psychological de-compensation and a breakdown in defences for some students (Klein, 1926). Bowlby (1969) argues that our early attachment patterns can be reactivated in times of psychological distress and in social or relationship crises and that the disruption of these patterns in later life can bring forth a breakdown of defences and the onset of depressive feelings. Bowlby (1979) postulates that secure attachment to the mother stems from the mother’s consistent and sensitive provision of security and love, thereby creating a healthy emotional bond, which includes a tolerance of separation. Bowlby’s (1979) view suggests that the ability to separate without experiencing distress seems to be what some students have difficulties with when they leave home to start University.

Bowlby hypothesises that mothers who are not attuned to the infant’s needs tend to lack warmth; they respond to the infant erratically and this leads to insecure attachments, which can be categorised as disorganised, ambivalent and avoidant (Bowlby, 1969; Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985). The result is that these insecurely attached individuals are the ones who, in later life, are more likely to experience difficulties in interpersonal transactions when building and maintaining relationships, which can lead to psychological problems. Research has demonstrated that certain types of attachments are associated with particular psychopathologies, ranging from self-esteem issues to depression, together with deep seated feelings of worthlessness (Zuroff & Fitzpatrick, 1995).

Stressing how attachments are re-activated in times of stress, Bowbly (1988) argues that

A feature of attachment behaviour of great clinical importance and which is present, irrespective of the age of the individual concerned, is the intensity of the emotion that accompanies it. The nature of the emotion aroused appears to depend on how the relationship between the individual attached and the attachment figure is faring. If it is threatened, there is jealousy, anxiety, and anger. If broken, there is grief and depression (p.4).

Bowlby’s assertion explains how a disruption or breakdown in attachments can be traumatic, leading to a complex set of painful feelings. Bowlby (1980) declares that “intimate attachments to other human beings are the hub around which a person’s life revolves, not only as a toddler but throughout adolescence and the years of maturity into adulthood and old age” (p. 442). This would explain why disruption of attachment patterns in the late adolescent stage can be so challenging for some individuals.

Can psychoanalytic theories and attachment theories inform each other?

Psychoanalytic paradigms, particularly object relations and attachment theories paradigms, are not natural bedfellows. This seems to stem from the history of the evolution of both disciplines. It is known that Bowlby deviated from the mainstream object relations theories, with his greater emphasis on external behaviours, parent-infant emotional bonds, the infant’s reaction to separation and loss and interpersonal relationship (Bowlby, 1969; Bowlby, 1973). Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, places greater emphasis on the internal world, including fantasies and internal dynamics, with less emphasis on observable external experiences.

The strength of Bowlby’s attachment theories lies in his embracing of empirical research in his work with mothers and babies, which was continued by Ainsworth (1973; 1974) and Main et al. (1985). Attachment theories have retained a solid presence in various disciplines and are widely embraced in developmental psychology, neuroscience, and in social psychology, where they have been useful in determining the quality of romantic relatedness in partners (Hazan and Shave, 1994). Longitudinal studies in attachment behaviours, for example, Grossman and Grossman, (1991) and Waters, Merrick, Albersheim, and Treboux, (1995) identified their appeal in psychoanalysis as a means of conceptualising psychopathology.

In recent times, there has been a gradual push for an interdisciplinary dialogue between psychoanalytic theories and attachment theories to inform research and clinical practice. Levy and Blatt (1999) argue that despite the fundamental differences, the psychoanalytic concept of ‘mental representations’ and attachment theories of ‘internal working models’ are analogous, as they are both developmental theories based on the early maternal-infant relationship, which shapes personality development and adult psychopathology. Psychoanalysis can therefore contribute to the study of attachment theories through the identification of developmental levels of representations, the degree of differentiation and internalization. Levy and Blatt (1999) view the application of psychoanalytic object relations theories to attachment theories as “providing an elucidation of interpersonal functioning within the insecure attachment types, thereby giving attachment theory a broader application, clinically and non-clinically” (p. 558).

A contemporary theorist, who is robustly engaged in integrating psychoanalytic and attachment theories clinically and through research, is Fonagy, who argues that the two theories are compatible, as they are both fundamentally based on the importance of parent-infant early relationship (Fonagy, 2001). Fonagy and Target (1996) coined the concept of mentalization, which embraces both attachment and psychoanalytic theories. Fonagy, Gerglely, Jurist, and Target (2002) define mentalization as the ability to reflect on others’ thoughts, beliefs, desires, and feelings, while also subjectively reflecting on one’s own mental state and how it may influence others. Mantalization capacity, developed in infancy, enables the infant to experience emotional regulation and inter-subjectivity. Failure to develop these abilities causes psychopathology in later life.

Fonagy et al. (2002) suggest that mentalization, usually attained at around 4-6 years old, indicates a secure attachment between the infant and its carer, while a lack of resolution signifies disturbed attachments. The differentiation of ego, the ability to recognise others as separate and mature object relations, are all ego capacities which are key to mentalization and are deeply embedded in the psychoanalytic discourse. Fonagy argues that the inability to experience inter-subjectivity or to affect regulation difficulties are the result of insecure attachment, which leads to psychopathology in later life (Fonagy, 2001). Psychoanalysis places greater emphasis on the mother’s emotional availability and her ability to tolerate the infant’s distress without feeling overwhelmed, to modify it and hand it back in a tolerable form, a process called containment (Bion, 1962).

Another major development in drawing psychoanalysis and attachment theories together is in the development of Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy (DIT). DIT was developed by Lemma et al. (2010) through an amalgamation of attachment theories, object relations theories and mentalization theories (Fonagy, 1996). DIT views depression as a disturbance in interpersonal relational (attachments) and it also emphasises the importance of the interpersonal relationship (object relation) between the therapist and client, while working in the transference. DIT has recently been included in the NICE guidelines (NICE, 2011). This demonstrates how psychoanalytic theories and attachment theories can work together, enriching both disciplines clinically.

Case example 1.

‘Brian’ is a 19-year-old man, who has moved from a small city to study for an undergraduate degree. He is experiencing severe problems sleeping and is constantly worrying that his girlfriend, who he has left behind, is going to abandon him. He obsessively ruminates about her cheating on him, which upsets him, makes him feel guilty and triggers bouts of anxiety. His feelings, behaviour and thoughts are destroying his relationship with his girlfriend, who he claims to love deeply. Brian’s parents divorced when he was four after their relationship had become acrimonious. His father is estranged, but Brian is very close to his mother, who he calls daily. He was referred for the standard six CBT sessions for anxiety.

In session 1, Brian presented as an intelligent young man, who robustly asserted that “I need pure CBT; I don’t want to talk about my past life”, said in a rather defensive manner. Brian found it difficult having me teach him the model. He would talk incessantly and he frequently interrupted when I was speaking. It was difficult to reorient him to go through the pragmatics of CBT. He would not do any of the little homework I set him, citing that he was too busy with his course work. Brian flooded each session with descriptive narratives about how his anxiety was crippling him and how this made him feel inadequate. In my counter-transference, I felt rejected and excluded from his world. There was a palpable sense of Brian sabotaging each session and I began to be acutely aware of the time limitations of the therapy.

In session 3, having been overwhelmed by Brian’s relentless talking, poor engagement with CBT and his repeated reminders of how afraid he was of losing his girlfriend, I suggested this to him “I wonder whether your assertion about not wanting to talk about the past and your deep fear of losing your girlfriend might bring back some painful memories about your other losses, which might be difficult to face”. Brian stopped talking, sat back in his chair with his face down, and paused for several minutes. Then, tears welled up in his eyes and he began poignantly talking about how bereft he felt about his father leaving and how he had started to experience nightmares, which continued until the age of fourteen. The nightmares were of his annihilation by a powerful force coming through the roof and leaving him feeling extremely vulnerable.

Session 4, 5 and 6 were psychoanalytic in frame, with the objective of helping Brian understand his attachments, offering him a safe space to express his feelings about the loss of his father (broken attachment), confronting inadequacy in his current interpersonal relationship (an insecure attachment) and separation anxiety with his mother (ambivalent attachment). These sessions were quite different to the early ones and were very contained. Brian slowed down and engaged with his vulnerability, which had caused him to defend by controlling the trajectory of the therapy in the early sessions. Brian informed me that each time he left sessions three, four and five, he would go home and sob. He did not know the reason for his tears, but said that he felt “cleansed” afterwards.

My supervision confirmed my clinical impression that Brian’s loss of attachment with a primary carer (his father), at an early stage had created an internal working model of insecure attachments. Leaving home, breaking the attachments with his girlfriend and mother, and losing his father when young were all unconsciously and psychologically traumatic for Brian. This disruption in early object relations (Freud, 1917; Klein 1946) had led to interpersonal difficulties in his current life. Only when Brian had sessions with a psychoanalytic framework, could he understand the unconscious impact these losses had on him, as they allowed him to express some of the painful emotions he had felt, linked to the loss of his father.

From a CBT perspective, Brian held core beliefs that the people in his life would leave him and that he was ‘not good enough’. Hence, the anxiety that his girlfriend would leave and that he was ‘inadequate’. However, this alone would not be enough to address the source of these maladaptive core beliefs. Brian scored very low on all measures -GAD-7, PHQ-9, and University Treatment Outcome Summary. He went on to see a private psychodynamic psychotherapist for longer term psychotherapy following this episode.

A critical discussion of CBT versus psychoanalytic oriented therapies when working with students and current research

The vignette presented above is a single case which gives a snapshot of some of the typical issues with which students present and the common clinical therapeutic pattern. CBT, which focuses on the external world, can be limiting and therapeutically negative when working with the student client group who may be experiencing an internal loss and a reactivation of insecure attachment patterns (Bowlby, 1969). Whilst not denying the efficacy of CBT in certain scenarios, I believe that working with students often requires an interpersonal model that addresses the unconscious phenomena and a consideration of attachment and loss, as demonstrated in the presented case.

It could be argued that the clients seen in our service and in the case referred to above are seen for only six sessions and that this may be considered insufficient for drawing more general conclusions and therefore my hypothesis lacks validity. I acknowledge the legitimacy of this argument but I believe that there is urgent need for research, specifically with student client groups and modalities, which may strengthen the case for psychoanalytic approaches. Unfortunately, at present, there is no such research available to support the hypothesis I am making. However, Coren (1996) strongly argues that short term psychodynamic psychotherapy is preferable when working with students, suggesting that it minimises commitments and procrastination and limits the potential for pathologizing. Malan, Heath, Bacal, and Balfour (1975) acknowledge the therapeutic gains of a single assessment session in a psychodynamic framework, as it enables the client to understand the nature of their deficits and to embark on future planning to address them.

Searle et al. (2011) conducted an influential study, offering four psychodynamic psychotherapy sessions to young people aged 16-30, at the Tavistock and Portman. A total of 236 clients was seen. Outcome measures Youth Self Report and Young Adults Self Report forms were used before and after the intervention. The outcome data suggested that there were greater improvements in all subscales, with most improvement noted in the internalisation subscales. The results of this study are applicable to the adolescent/young adult student client group.

Blagys and Hilsenorth (2000) and Shedler (2010) looked at outcome of literature database research that identified features which distinguish psychoanalytic oriented therapies from other therapies. They argued that psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapy enables the client to explore their emotions and recurrent themes and allows an exploration of early attachments. They also declared that the strong therapeutic alliance in psychoanalytic oriented therapies enables an exploration of other interpersonal relationships. These features are highly relevant to the work with the student client group, many of whom are dealing with issues related to loss and a breakdown of attachments. Shedler (2010) also makes the important point that “intellectual insight is different to emotional insight” (p. 99). Often, students are intellectually aware of their problems, as in the case presented, but lack the emotional connection to address them. This drives the need for therapists to adopt a more flexible way of addressing clients’ difficulties, rather than focusing on one model.

Another key limitation of CBT with students is their aversion to homework. Most of the students seen are already struggling with completing their coursework. They do not take kindly to being given yet more assignments. The CBT model puts the therapist in the role of an educator or a metaphoric parent, who teaches the child the model. This is a source of angst among students, who are at a stage where they are seeking independence. Unlike CBT, psychoanalytic psychotherapy enables students to work through their loss by negotiating endings in therapy. (Lee, 2004) declares that endings when working with young adults are very important, as they help them deal with their own traumatic ending of childhood attachments.

Extensive research has demonstrated the efficacy of psychoanalytic oriented therapies. Leichsenring and Klein (2014)’s systematic review of psychodynamic therapy for specific disorders illustrated trough RCTs show that psychodynamic psychotherapy is effective. Abbas, Hancock, Henderson, and Kisely (2006) carried out a Cochrane database meta-analysis, studying the effects of short term psychodynamic psychotherapies with 23 RCTs, involving 1500 patients. The results showed greater reduction in symptoms, which was maintained in medium-long term post follow up. Leichsenring and Leibling (2007)’s systematic review on the efficacy of short to moderate term, manual guided psychodynamic psychotherapy, with 23 RCTs, concluded that psychodynamic psychotherapy was as effective as CBT and in some respects superior to it.

The study by Taylor (2008) suggests that psychodynamic psychotherapies were as effective as CBT, coupled with medication. Guthrie et al. (1999) studied the cost effectiveness of short term psychodynamic psychotherapy and demonstrated improvement in special functioning, fewer contacts with services, and reduced use of medication. Durham, Chambers, and Power (2005) carried out a study in Scotland on the durability of CBT, which concluded that effects of CBT erode over time and there is no advantage of CBT over other therapies.

Key psychoanalytic perspectives on psychopathology and their application to the student client group

Psychoanalytic theories enable us to understand the sources of psychological problems, but they can also give us an insight into the internal mechanisms of ego development, specifically the importance and complexity of the successive accomplishments of certain crucial developmental tasks. Failure to accomplish these developmental tasks is a key factor in psychopathology in later life (Klein, 1932; Fairbairn, 1944; Winnicott, 1945; Bion 1962). Psychoanalytic theories therefore enable us to formulate and conceptualise our clients’ difficulties, as well as identify the most appropriate treatment for them. This notion suggests that psychoanalytic oriented therapies are more likely to achieve positive outcomes than other therapies.

Klein (1932; 1946) argues that psychopathology in later life stems from the infant’s difficulties with negotiating the depressive position from the paranoid-schizoid position, in relation to the breast, its first object relation. Klein hypothesises that the infant must deal with primitive persecutory anxieties of a psychotic nature, due to the mother’s breast being experienced as both gratifying (good) but frustrating (bad) leading to its splitting into both a loved and hated object. Due to the death instinct, the infant develops annihilatory fears and as a result unleashes sadistic oral attacks on the satiating breast, which is also resented. Winnicott (1945) agrees with Klein’s idea that the infant’s early ego lacks cohesion and is susceptible to disintegration. Through the mechanisms of introjection of the good (loved) and bad (hated) breast, together with the realisation that the breast is one object, the infant’s ego becomes more integrated.

Having developed the awareness that the breast is one object and psychically introjecting it as a whole object, the infant is then able to transition into the depressive position, which is dominated by feelings of reparation, guilt, shame, and mourning. Klein (1945) asserts “The synthesis between loved and hated aspects of the complete object gives rise to feelings of mourning and guilt, which imply vital advances in the infant’s emotional and intellectual life” (p. 100). Until the infant negotiates the depressive position, the ego lacks cohesion and is vulnerable to disintegration. An individual’s personality, emotional life and psychopathology in later life are all shaped by how the infant negotiates the depressive position. Looking at depression as a psychological illness, Klein (1946) hypothesises that the “violent splitting of parts of the self into others is what causes depletion of the ego, triggering feelings of loneliness and depressive feelings” (p. 104).

Freud’s (1917) theory of mourning and melancholia is a cornerstone in understanding the psychogenic processes associated with normal mourning and pathological disposition of mourning, known as melancholia. Freud views normal mourning as a reaction to a loss-relationship, a loved person/object, including emigration away from the individual, which is in the consciousness. Normal mourning is associated with painful feelings and reality testing that the object has departed. As time goes on, the ego withdraws all its libido and attachments, becoming free again. One is then able to cathex the libido into a new object and is then capable of relating healthily to others. In line with Freud’s theory of mourning, following the loss of an object, Winnicott (1965) views an “inability to mourn and feel concerned as secondary to the infant’s inability to achieve maturation and integration of the self” (p. 220).

In melancholia, the sufferer cannot perceive what is lost and it remains in the unconscious. What distinguishes melancholia from normal mourning is the “profound painful dejection, cessation of interest in the outside world, loss of capacity to love, inhibition in all activities, a lowering of self-regard, self-reproachment and a delusional expectation of punishment to the self” (Freud, 1917, p. 252). In melancholia, the ego becomes consumed by these feelings and is severely impoverished. This leads to a splitting of the ego, where part of the split-off ego becomes the lost object. Freud believes that withdrawal of the libido into the ego and the splitting of the ego, which is identified with the lost object, is what leads to the sadistic attacks on the lost object, which is also the self.

According to Freud, that fixation, the narcissistic object relation, and ambivalence towards the same object are key factors which lead to lack of conscience and berating of the split- off self. Freud views melancholia, and other neurotic psychopathologies as complexities in the object relationship, which cause a disturbance of the normal process of dealing with loss. Fairbairn (1941) agrees with the idea of ambivalence in object relation, causing psychological disturbances in asserting that “difficulties with schizoids is how to love without destroying by love and with depressives is their inability to love without destroying by hate” (p. 271).

As pointed out earlier, many students leave home to start university in their late adolescence, which is identified as one of the key stages of developmental achievements in psychoanalytic theories, due to the complexities related to mourning the loss of the child and transitioning into adulthood, which also involves “loss of one’s position in the family” (Brice, 1982, p. 317). Wolfenstein (1966) argues that each developmental stage involves mourning the loss of the old self. Every experience is unique and not everyone goes through these complex stages smoothly. Psychoanalytic theories suggest that glitches in these processes could contribute to adult psychopathology. It appears that students, who are in the adolescent stage, are already developmentally vulnerable. The loss through leaving home and the consequent challenges in attachments, compound the complexities of this stage, triggering a psychological breakdown. Blos (1967) views the adolescent stage as the ‘second individuation stage,’ where the adolescent disengages from infantile love objects to cathex the libido into more mature object relations. This psychological leap from child to adult is what makes adolescence particularly complex.

Freud’s key developmental theory postulates that the infant develops through oral, anal, latent and adolescent stages before reaching the adult stage of psychological maturity (Freud, 1905). However, there is now evidence in neuropsychology that the human brain continues to grow into the early 20s (Dahl, 2004). This gives weight to the idea that, though adolescents (students) might appear physically mature, they may be underdeveloped mentally, cognitively, and psychologically and are consequently lacking the ego strength to deal with emotionally challenging situations.

The transitioning into adulthood from the adolescent stage also evokes some very deep-seated issues related to adaptive character formation and establishing oneself as an individual (Blos, 1968, p. 250). (Frankl and Hellman, 1962; Laufer, 1966) all assert that the adolescent’s separation from parents leads to a mourning process, as the adolescent must libidinally detach themselves from the parents, as they transition into adulthood. Laufer (1966) goes on to suggest that in response to failure to mourn the originally attached parental, oedipal relationship, additional defences are employed, particularly in adolescence, leading to a distortion of reality (p. 288). This view gives an insight into some students’ internal difficulties.

Conclusion

Delivering psychotherapy interventions to students is a specialism, which considers the nature of their difficulties, which are, in most cases, linked to internal loss and a breakdown of attachments. In the current climate, CBT is being prescribed for most students, as it is considered effective and is evidence based. However, the difficulties experienced by some students as identified in this paper, can be best worked with and reframed from a psychoanalytic perspective, which addresses the unconscious dynamics. Understanding the impact of loss of attachments on individuals is crucial, as are the psychogenic processes in the adolescent developmental stage. Psychoanalytic theories and attachment theories have been seen as complementing each other, both clinically and in research. This paper concludes that the therapist needs to develop an open mind, regarding the model that is used when working with adolescent students, but strongly advocates psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies. Employing an approach such as CBT, which treats symptoms without addressing the origins of the client’s difficulties is an inadequate response to their problems. Psychoanalytic trained therapists need to garner more research evidence to give greater credibility to claims of the efficacy of psychoanalytic oriented psychotherapies with specific client groups and pathologies, putting it on a par with CBT. Research has already suggested that psychoanalytic psychotherapies are effective. The introduction of DIT in the NICE guidelines hopefully marks the beginning of a change in clinical practice which may lead to widespread acceptance of the valuable contribution which psychoanalytic psychotherapy can make in the treatment of the specific client group discussed in this paper.

Bibliography

Abbass, A. A., Hancock, J. T., Henderson, J., and Kisely, S. (2006). Short term psychodynamic

psychotherapies for common mental disorders. Cochrance Database of Systematic Reviews: Issue 4.

Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M.C., Waters, E., and Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Hillsdale,

New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum associates.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social behaviour: Socialization as a

product of reciprocal response to signals. In: The integration of a child into a social

world, ed M.P.M. Richards. London: Cambridge University Press, pp 99-135.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1973). The development of infant-mother attachment. In: B. Cardwell and

- Ricciuti (Eds.), Review of child development research, Volume 3 pp.1-94. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Beck, J. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guildford Press.

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. London: Heinemann.

Blagys, M. D. and Hilsenroth, M. J. (2000) Distinctive features of short-term psychodynamic

interpersonal psychotherapy: A review of the comparative psychotherapy process literature. Clinical Psychology, Volume 7 (2): 167-188.

Blos, P. (1967). The second individuation process of adolescence. Psychoanalytic study of the

child, 22: 162-186.

Blos, P. (1968). Character formation in adolescents. Psychoanalytic study of the child, 23: 245-

263.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base. New York: Basic books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: sadness and digression. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Separation: anxiety and anger. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London: Tavistock Publications.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Volume 1. Attachment. London:

Hogarth Press.

Brice, C.W. (1982). Mourning throughout the life cycle. American Journal of Psychoanalysis. 42:

315-325.

Coren, A. (1996). Brief therapy-base metal or pure gold? Psychodynamic practice. 2 (1): 22-38.

Cooper, M. (2011) The challenge of counselling and psychotherapy research. 22 (4): 10-16.

Dahl, R.E. (2004). Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Annuals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1021: 1-22.

Durham, R. C., Chambers, J. A., and Power, K.G. (2005). Long term outcome of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) clinical trials in central Scotland. Health Technology Assessment, 9:1-174.

Fairbairn, W. R. D. (1944). Endopsychic structure considered in terms of object relationships. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 25:70.

Fairbairn, W.R.D. (1941). A revised psychopathology. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 22: 271.

Fonagy, P. (2015). The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: An update. World Psychiatry, 14 (2) :137-150

Fonagy, P. and Luyten, P. (2009). A developmental mentalization based approach to the understanding and treatment of borderline personality disorder. Development and psychopathology, 21 (4), 1355-1381.

Fonagy, P., Gerglely, G., Jurist, E., and Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalisation and the development of the self. New York, NY: Other Press.

Fonagy, P. (2001). Attachment theory and psychoanalysis. USA: Karnack.

Fonagy, P. (1996). Associations among attachment classifications of mothers, fathers and their infants. Evidence for relationship specific perspective. Child Development. 67: 541-555.

Fonagy, P. and Target, M. (1996). Playing with reality: Theory of the mind and normal development of psychic reality. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 77: 217-223.

Fonagy, P. (1991). Some thinking about thinking: Some clinical and theoretical considerations in the treatment of a borderline patient. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 72: 1-18.

Frankyl, L. and Hellman, I. (1962). The ego’s participation in the therapeutic alliance. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 43: 333-337.

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and Melancholia. Standard Edition, 14: 251-268.

Freud, S. (1915). A case of paranoia running counter to the psychoanalytic theory of the disease. Standard Edition, 14: 261-272.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on sexuality. Standard Edition, 7: 123-245.

Greenberger, D. and Padesky, C.A. (1996). Mind over Mood. Guilford Press.

Grossman, K. E. and Grossman, K. (1991). Attachment quality as an organisation of emotional behaviours and responses in a longitudinal perspective. In: Attachment across the life cycle, Ed. C.M. Parkes, J. Stevenson-Hinde, and P. Marris. London: Tavistock/Routledghe, pp. 93-114.

Guthrie, E., Moorey, J., Margison, F., Barker, H., Palmer, S., McGrath, G., Tomenson, B, and Creed F. (1999). Cost effectiveness of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy in higher utilisers of psychiatric services. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56: 519-526.

Hazan, C. and Shaver, P.R. (1994). Attachment as an organisational framework for research on close relationships. Psychology Inquiry, 5: 1-22.

Hinshelwood, R. D. (2010). Psychoanalytic research: Is clinical material any use? Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. Vol 24, No 4, 362-379.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27: 99-110.

Klein, M. (1932). The psychoanalysis of children. London: Hogarth Press.

Klein, M. (1926) The foundations of child analysis In Psychoanalysis of children. London: Hogarth.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L. and Williams, J.B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General and Internal Medicine, 9, 606-613.

Knox, J. (2013). The analytic institute as a psychic retreat: Why we need to include research evidence in our clinical training. British Journal of Psychotherapy. 29 (4) 424-448.

Lamb, C., Hall, D., Kelvin, R., and Van Beinum, M. (2008). Working at the CAMHS/Adult Interface: Good practice guidance for the provision of psychiatric service to adolescents /young adults. A joint paper from the Child and Adolescent Faculty and the General and Community Faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Layard, R. (2006). The case for psychological centres. British Medical Journal, 332, 1030-1032.

Laufer, M. (1966). Object loss and mourning during adolescence. Psychoanalytic study of the child, 21: 269-293.

Leahy, R. (2003). Cognitive Therapy Techniques: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guildford.

Leichsenring, F. and Klein, S. (2014). Evidence of psychodynamic psychotherapy in specific mental disorders: A systematic review. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy (in press).

Leichsenring, F. and Leibling, E. (2007) Psychodynamic psychotherapy: A systematic review of techniques, indications, and empirical evidence. Psychology and Psychotherapy, Research, and Practice. 80: 217-228.

Lemma, A., Roth, A., and Pilling, S. (2008). Psychoanalytic/ Psychodynamic Therapy: competences framework Retrieved on December 2, 2016 from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/pals/research/cehp/research-groups/core/competence-frameworks/Psychoanalytic-Psychodynamic-Therapy.

Lemma, A., Target, M., and Fonagy, P. (2010). The development of brief psychodynamic protocol for Depression: Dynamic Interpersonal Therapy (DIT). Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 24, 329-346.

Levy, K.N. and Blatt, S.J. (1999). Attachment theory: Further differentiation within insecure

attachment patterns. Psychoanalytic Enquiry, 19: 541-575.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., and Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A

move to the level of representation. Monogr, Soc. Dor Res. Child Development. 50: 1-2, Serial number 209, 66-104.

Malan, D.H. (1979). Individual psychotherapy and the science of psychodynamics. London

Butterworth.

Malan, D.H., Heath, E.S., Bacal, H, A., and Balfour, F. (1975). Psychodynamic changes in untreated neurotic patients. 11. Apparently genuine improvements. Archives of General Psychiatry. 32 (1):110-26.

McLeod, J. (2011). We need good quality non RCT evidence. Therapy Today. 22 (7): 16-7.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence [NICE] (2011). Common mental health problems: identification and pathways to care. Retrieved on December 10, 2016 from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123/resources/common-mental-health-problems-identification-and-pathways-to-care-35109448223173.

National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2009). Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults. (Partial update of NICE clinical guidance 23). London: Author.

Norcross, J.C., Beutler, L.E., and Levant, R.F. (2005) Evidence based practices in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental questions. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association.

Orlinsky, D.E. and Howard, K.I. (1986). The relation to process and outcome in psychotherapy.

In A. Bergin S. & Garfield Editions, Handbook of Psychotherapy, and behaviour change, 2nd Editions. New York: Wiley.

Searl, L., Lyon, L., Young, L., Wiseman, M., and Foster- Davis, B. (2011). The young people’s consultation service: An evaluation of very brief psychotherapy. British Journal of Psychotherapy. 27 (1): 56-78.

Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 65 (2): 98-109.

Spitzer, R.L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J.B. & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092-1097.

Taylor, D. (2008). Psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapies for depression: the evidence base. Advances in psychiatric treatment, 14: 401-413.

Waters, E., Merrick, S. K., Albersheim, W., and Treboux, D. (1995). Attachment security from infancy to early adulthood: A 20-year longitudinal study. Poster presented at the biennial meeting of society for Research in Child Development, Indianapolis, IN.

Winniccott, D.W. (1965). The maturation process and the facilitating environment. New York: International Universities Press.

Winnicott, D.W. (1960). The theory of parent/infant relationship. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 41: 585-595.

Winnicott, D.W. (1958). Through paediatrics to psychoanalysis: Collected papers. London: Tavistock.

Winnicott, D.W. (1953). Transitional objects and transitional phenomena- A study of the first not me possession. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 34: 89-97.

Winnicott, D. W. (1945). Primitive emotional development. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. 26: 137.

Wolfenstein, M. (1966). How is mourning possible? Psychoanalytic Study of Children. 21: 93-123.