COPYRIGHT - CITY SANCTUARY THERAPY

No part of this website, including the blog content may be copied, duplicated, or reproduced in any manner without the author’s permission. Any information, materials, and opinions on this blog do not constitute therapy or professional advice. If you need professional help, please contact a qualified mental health practitioner.

Why are some people emotionally sensitive than others, & why do some people experience emotional difficulties more than others? There are a range of personality tests, for example- the Myers Briggs, SAPA Project Personality Test, Helen Fisher Personality Test, and Ennegram Personality Tests. Each one of them reveals that we are all unique, and we have varied traits and personality types. Even identical twins who grew up in the same environment, and had similar experiences throughout life will never have identical personalities. Within these personality domains, we all have our strengths and weaknesses. Having high intellectual abilities does not correlate with high emotional intelligence. Paradoxically, it is often the case that people who are highly intelligent struggle with understanding and making sense of their emotions. This may be because while they have developed their intellectual capabilities, their emotional abilities are not as developed. Personality is not something we acquire; it’s something we develop throughout our lives. The formative years are crucial to personality development and some people’s emotional challenges in adulthood are directly related to a combination of environmental and psychological factors in their upbringing.

Despite growing up in the same environment, siblings do not always turn out the same. Some turn out to be more emotionally buoyant and robust than others, who may be more sensitive or have difficulties managing emotions. We may have siblings who developed some mental health challenges-anxiety, depression, Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorders/Borderline Personality Disorder, or just struggle with regulating emotions. Or we are that person. It can be distressing to have a sibling who experiences emotional difficulties, or to be that person who suffers from mental health problems and or emotional difficulties. In some cases, it often leads to parents and siblings blaming themselves, or each other for causing these difficulties. Some parents tend to view their children developing emotional difficulties as a sign of failure in their parenting. This is a key reason why some people who may have been raised in homes where they had everything they needed environmentally and economically, struggle with seeking help. There is often a sense of guilt attached to their struggle, and they feel that they do not have the right to struggle. To them it also means they have failed or translates to their parents having failed. It’s as if they have no right to complain, struggle or suffer. Yet they are only human. Children need more than just economic provision. Emotional warmth, nurturance, co-regulation with adults, emotional safety, and adults who are emotionally attuned to the developing infant are all key to how we develop our ability to emotionally regulate as adults.

How do we develop emotional difficulties in adulthood

1- Biology

Biology (genetics) plays a big part of our makeup. Epigenetics is the study of how changes in the external or internal environment impact gene expression. Fonagy views our capacity to seek attachments as part of our biology and genetic inheritance. He considers that there is a gene- environment interplay which shapes how we develop biologically. The environment is the attachment relationship. Neuroscience research proves that sensitive people have certain gene variations which create activity in certain brain regions. Martin Teicher researches on child abuse and maltreatment argues that “Brain development is directed by genes but sculpted by experiences” (p652). This means that our genetic make up is shaped by our environmental experiences.

2-Psychological

Childhood trauma-abuse, neglect, prolonged stress in early life, childhood illness, early loss through death or separation. Research suggests that people who experienced adverse childhood experience are likely to struggle with their emotions and develop severe mental health difficulties in adult life (Young Minds, 2018; Bellis et al, 2014). 1 in 3 people with mental health problems had adverse childhood experiences. Read my blog post on Adverse Childhood Experiences where there is more information about ACEs. Though his pioneering work Allan Schore evidences that the brain development of people who are brought up in environments where there is trauma and maltreatment is significantly different to those who were raised in more nurturing environments. He considers the emotional relationship between child and caregiver as the environment for brain development and that brain development is an adaptation to that environment. Allan Schore's (2000) research highlights the likelihood of people who have experienced childhood trauma experiencing mental health challenges in adult life. He terms this ‘relational trauma’ bound in the traumatogenic experiences happening within the ordinary transactions between parent and baby in the course of looking after the baby.

2- Environment

The environment we grow up in plays a huge part in how we manage emotions as adults.

Environments where children grow up with adults who are emotionally dysregulated themselves only lead to adults who are unable to regulate emotions emotionally. “You cannot speak a language you never learnt”.

Environments were adults invalidate the children’s feelings & the child is made to hide their true feelings (sadness/shame, anger etc) lead to adults who never learnt to bear difficult feelings.

Environments where the child has to constantly tune into the parents’ own emotions, ie disregarding their own emotions.

Environments where the parent is absent from the child’s emotional landscape -emotional neglect.

An environment where healthy emotional expression and emotional regulation was modelled is key to healthy emotional development and expression in adult life. Psychological trauma also predisposes some people to having difficulties with their emotions. Psychoanalytic theories put greater emphasis on the ability of the parent to offer a form of emotional containment (Klein, 1946; Bion, 1962). They give value to a care giver who is emotionally attuned (good enough mother) and creates an environment (Winnicott, 1960) where the child can feel emotionally held by the parent. Without this, the child never develops the capacity to manage difficult emotions, which should be moderated by the parents, and handed back in a palatable and less toxic form- Bion calls this "containment". Winnicott (1960) also uses the concept of mirroring where the baby develops reflective abilities through the mirroring of mother's affective states and learn to emotionally regulate as a result- omnipotence- and integrate the mother as a good object . The mother has to be attentive and attuned to the baby's emotional states; in some cases the mother fails to facilitate the mirroring process which has negative consequences on the baby's developing psyche.

Attachment and Affect Regulation

Through his scientific research work, Peter Fonagy proposes that we have an inbuilt biological evolutionarily advantageous potential for an interpersonal interpretive capacity: the capacity to ‘read’ and understand the mental states of others and our own (Fonagy, 2000). He terms this mentalisation. However this capacity can been diminished as a result of prolonged exposure and adaptation to an ongoing stressful caregiving relationship in childhood. This interruption often creates difficulties in understanding and attuning to other people's affective states in adulthood- inability to mentalise, and difficulties with emotional regulating. This is indeed a form of relational trauma which stems from a mother not responding to the baby's affective states, and therefore not developing the capacity to regulate affect. Fonagy developed a therapy approach called mentalization which is essentially learning to develop the capacity to reflect on one's affective state and that of others. Fonagy's mentalization approach is commonly used in the treatment of BPD and it has demonstrated positive result. Most people's struggle with emotions is due to their inability to emotionally regulate, and to reflect on their affective states, and that of others- mentalise. This has a huge impact on interpersonal relationships, and managing one's own emotional reactions. The capacity to mentalise is rooted in the child's attachment relationship with their care giver, and it is something that can change throughout one's lifespan.

Neuroscience

Allan Schore's work on brain development and emotional growth, highlights the significance of affect regulation, which is developed in childhood. He views the capacity to manage emotional states as a neuropsychobiological developmental achievement, arising out of the early mother-infant relationship. In normal development, the child learns to regulate their own emotions, initially through a process of co-regulation with the (maternal) care giver . Schore considers the capacity to experience, communicate, and regulate emotions as key milestones in the development of the human infant, which is heavily dependent on the quality of the relationship with the care giver. Pathology develops when the child is left in heightened emotional states, leading them to develop maladaptive ways of coping with emotions, something that continues in adulthood. The interaction between brain development and the environment which is seen as key. Schore links the infant's right brain maturation- ability for affect regulation- giving significance to the early interpersonal affective experiences with care givers. This development has an impact on other parts of the brain-limbic system- which deals with processing the processing of physiological and cognitive components of emotion. Schore centres human emotional development to the ability for the brain to self organise, and the infant to interactively regulate.

Alexithymia and Autism

Some people do not experience emotions at all, a condition called Alexithymia. Some, but not all people who are on the autistic spectrum experience difficulties with experiencing certain emotions, such as empathy. Alexithymia and Autism are two distinct conditions; however some people who are Autistic can also be Alexithymic. Like Autism, Alethythimia has a spectrum. Some people may have the trait (primary) or secondary Alethithymia where it is situational- for example where there is trauma, PTDS symptoms may lead to the subject experiencing difficulties identifying their emotions. Anyone who is Alexithymic lives in a world where there are no emotions, and they rely on their cognition to make sense of the world. They may be able to say "l love you", " l am sorry", etc but they are not able to emote, or relate any of their life experiences to an emotion. Their bodies do not respond to any emotional states- for example anger means heart racing, anxiety means restlessness, sadness means tears etc. This must make their world both obtuse and abstract. The lack of emotion creates a lot of challenges in interpersonal, and romantic relationships. Resultantly, people with Alexithymia are very vulnerable to having relationship problems, and depression. Alethythimia is associated with trauma, and extreme emotional neglect in childhood. One may hypothesise that the emotional blankness may be a result of a defence the person created as a child, in an environment where there was emotional neglect or trauma (Klein, 1946). This defence then becomes part of ones personality, and remains present in adulthood.

Emotional sensitivity or having difficulties managing emotions is not a sign of weakness. Having relationships where our feelings are validated & checking in with oneself is crucial. Knowing one’s vulnerabilities- what’s likely to bring out the sensitivity can also help in mitigating it.

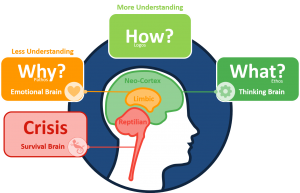

Logic of Emotions -Triune Brain Theory

Dr Paul McLean proposed the evolutionary brain theory back in the 1960s- see image below. Today, this theory is widely accepted in the field of psychology. He viewed the brain as having three main layers, superimposed on each other, which developed at different stages in our evolution. Viewing the brain as an entity that is composed of these 3 layers, helps us understand why sometimes we do things that are contradictory to how we feel, and that defies our usual way of doing things. This is so because our behaviour is at times controlled by our reptilian brain (behaviour-reflex), or our creature brain (emotional response). Recent studies have concluded that neurons in many parts of the brain continue to undergo structural change not just through childhood and adolescence, but throughout life- any new experiences, at whatever age, can cause the brain to physically alter its synapses-a characteristic known as neuro-plasticity.

The Truine brain model also helps us understand why some people struggle with managing emotions, which means they have not nurtured, and not fully developed their emotional (middle) part of the brain. This can be done, and therapy helps. Today’s society values reason over emotion, people who experience difficulties regulating emotions are often left feeling alienated and misunderstood. Emotions have their own logic, quite distinct to the logic of intellect. Its vital that we comprehend the logic of emotions.

Triune Brain Illustration (Image credit to Dimitri Roman)

Reptilian/ Mammalian

This is primitive and innermost part of the brain which deals with instinct, survival, safety, territory and repetition. It’s the part that is reflexive and triggers the fight, flight, freeze, reactions when there is perceived or actual danger. We inherit this brain from all the animals in the animal kingdom, which we are a part of. For example, if there is a loud bang, the mammalian brain triggers a response for us to either run (flight), freeze (hide) or find out where the bang is coming from (fight). This part of the brain is what creates most difficulties in interpersonal relationships, where people are reactive, not reflective.

Limbic Brain- Creature Brain

This covers the mammalian brain and is more sophisticated. Also called the creature brain, it is the part that emotes, and helps us make emotional connections to experiences. It helps us make sense of our senses-pleasure pain and enables us to nurture, experience humour, grief, playfulness and other social experiences. It also handles our behaviours and motivations and helps us make connections between experiences and emotions. We experience a range of emotions through this part of our brain. It’s the part that is also able to make sense of the need to keep away from things that brings us displeasure and draws us to things that brings us pleasure. Using the example given above of hearing a loud bang-this part of the brain helps us recognise the feeling it evokes-fear, anxiety etc

Neo Cortex

This part of the brain is the recently evolved part, and it’s the part that deals with anything intellectual, logic and reasoning. It deals with facts- why, how and make sense of the world in a logical manner. This part is highly developed for many people as it can be developed through learning and exercising our intellectual abilities. Drawing on the example of the loud bang, its the part that seeks to investigate what caused the bang, why, where and make sense of it.

Discussion- Therapy and Emotional Maturity

Using the Triune theory, people who struggle with emotions have not fully developed the emotional part of their brain and this could be for several reasons. The environment is primary to how we learn to relate to emotions, so is our biological make up, although (l believe) this is secondary. In many cases, it also means that the intellectual part of their brain is very well developed, while the emotional part has not been sufficiently developed. The primitive part of the brain is something we cannot change. However, we can learn to tame it if we use the emotional, and intellectual part of our brain and make sense of situations that are perceived as threatening. This philosophy informs Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (Aaron Beck), as well as Mindfulness.

Peter Fonagy’s Mentalisation Based Therapy (MBT) approach which is based on developing the capacity to reflect on the affective mental states could also be seen as a way of expanding emotional repertoire, therefore developing an understanding of one’s emotional states in relation to others. Mentalisation Based Therapy (MBT) is a free standing therapy approach used to treat people with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD)- where people experience huge difficulties regulating emotions and inability to reflect on their mental state and that pf others- mentalise. I believe that therapy per-se, has some mentalisation aspects, where there is fostering of the capacity to reflect on one's emotional states and triangulation of experiences.

Regardless of modality, my view is that therapy as a reflexive process, helps people develop emotional maturity. It helps people nurture and develop their emotional vocabulary & expand it. Therapy also helps with developing the capacity to mentalise- reflect on one's mind, the mind of others, as well as regulate emotions. Therapy enables us to re-establish broken attachment patterns and restore healthy ways of relating (form a secure attachment), in a secure and safe way-this is why the relationship with the therapist is central. Neuroplasticity- the capacity for our brain to adapt and change over time throughout our life span mean that we can learn healthier ways of relating, and rebuild new pathways to emotionally responding to situations. Therapy enables us to develop an intimate relationship with our emotions & own how we response to them. There is a difference between responding & reactivity- the former is healthier, while the later is a more primitive way of handling emotions. If we learn that we have other options, and not simply repeat, but reflect on our feelings, we are indeed nurturing that emotional part of ourselves.

I always view therapy as a process where some people who feel strongly need help to understand their feelings and emotions, while others who understand need help to feel. Emotions enriches our lives-they make it colourful and beautiful. Without emotions, our lives are grey and gloom- we wont feel joy, excitement, sadness, anger, anxiety, which makes us feel alive and shapes life. However they become problematic when they diminish the quality of our lives due to either overwhelm, lack of, or inability to regulate them.

Interestingly, mildly stressful experiences of novelty, and complex enriched environments in childhood, can enhance our ability to cope with more complex emotions in adulthood, -adaptive advantage- and help us build emotional resilience.

This paragraph is from Thomas Ogden’s Book Chapter- On Potential Space- in Spelman et al book referenced below. It highlights the mother-infant, and environment context and the functions of the mother in helping the infant regulate emotions.

“Within the context of the mother–infant unit, the person who an observer would see as the mother, is invisible to the infant and exists only in the fulfilment of his need that he does not yet recognise as need. The mother–infant unity can be disrupted by the mother’s substitution of something of herself for the infant’s spontaneous gesture. Winnicott (1952) refers to this as “impingement”. Some degree of failure of empathy is inevitable and in fact essential for the infant to come to recognise his needs as wishes. However, there does reach a point where repeated impingement comes to constitute “cumulative trauma” (Khan, 1963; see also Ogden, 1978). Cumulative trauma is at one pole of a wide spectrum of causes of premature disruption of the mother–infant unity. Other causes include constitutional hypersensitivity (of many types) on the part of the infant, trauma resulting from physical illness of the infant, illness or death of a parent or sibling, etc. When premature disruption of the mother–infant unity occurs for any reason, several distinct forms of failure to create or adequately maintain the psychological dialectical process may result: (1) The dialectic of reality and fantasy collapses in the direction of fantasy (i.e., reality is subsumed by fantasy) so that fantasy becomes a thing in itself as tangible, as powerful, as dangerous, and as gratifying as external reality from which it cannot be differentiated. (2) The dialectic of reality and fantasy may become limited or collapse in the direction of reality when reality is used predominantly as a defence against fantasy. Under such circumstances, reality robs fantasy of its vitality. Imagination is foreclosed. (3) The dialectic of reality and fantasy becomes restricted when reality and fantasy are dissociated in such a way as to avoid a specific set of meanings, for example, the “splitting of the ego” in fetishism. (4) When the mother and infant encounter serious and sustained difficulty in being a mother–infant, the infant’s premature and traumatic awareness of his separateness makes experience so unbearable that extreme defensive measures are instituted that take the form of a cessation of the attribution of meaning to perception. The dialectic of reality and fantasy becomes restricted when reality and fantasy are dissociated in such a way as to avoid a specific set of meanings, for example, the “splitting of the ego” in fetishism. (4) When the mother and infant encounter serious and sustained difficulty in being a mother–infant, the infant’s premature and traumatic awareness of his separateness makes experience so unbearable that extreme defensive measures are instituted that take the form of a cessation of the attribution of meaning to perception. Experience is foreclosed. It is not so much that fantasy or reality is denied; rather, neither is created. (These four categories are meant only as examples of types of limitation of the dialectical process. In no sense is this list meant to be exhaustive.) Pages 124-125

References

Bion, W. R. (1962). Learning from experience. London: Heine-mann. Reprinted by Karnac 1984, ‘’The K-link,” pp. 89–94. By permission, Karnac Books.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on Some Schizoid Mechanisms. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 27, 99-110.

Bellis, M.A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N. (2014). National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med 12, 72 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-12-72

Fonagy, P. and Target, M. (2000) Mentalisation and personality disorder in children: a current

perspective from Anna Freud Centre. In Lubbe, T. (ed.), The Borderline Psychotic Child, 69–89.

London: Routledge.

Ogden T. (2014)On Potential Space: in Spelman, M. B., & Thomson-Salo, F. (Eds.)The Winnicott tradition : Lines of development-evolution of theory and practice over the decades. Taylor & Francis Group.

Young Minds (2018). Addressing Adversity; Prioritising adversity and trauma-informed care for children and young people in England. Mental Health Review Journal.

Schore, A.N. (2000) Early relational trauma and the development of right brain. Unpublished invited presentation. London: Anna Freud Centre

Winnicott, D. W. (1960). The theory of the parent–infant relationship. In: The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment (pp. 37–55). New York: International University Press, 1965.

Image Credit- Nathan Dimlao-Unsplash